May 8, 2020 | By Paul Spencer, CPC, COC

Time, as it applies to procedures and services, is a vastly misunderstood portion of the Resource Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS), the methodology used to generate the relative value units (RVUs) that determine the payment for every CPT code. For many years, information on the average time for procedures and services, as measured by CMS, was not readily available for analysis. Almost 10 years ago, this changed.

Despite this information now being available at the click of a mouse, I continue to encounter professionals in our industry who do not realize that as part of each year’s Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) final rule, CMS includes an Excel spreadsheet called “CY 20XX PFS Final Rule Physician Time.” This file is available as one of many downloads available here. The spreadsheet contains median service times for each and every CPT code. These times are determined by the Harvard-RUC Time Study, a three-year rolling survey of practitioners that gathers information from providers regarding how much time procedures and services normally consume. It is important to note that “median time,” by definition, is the middle number in a data set. Median is selected as part of the time study in order to ensure that any outliers in the data do not skew the average of all values.

There is a reason why this information was made available by CMS. A few years ago, an idea was floated in the annual proposed rule to eliminate global surgery as a concept for the reimbursement of services. This stemmed from two HHS/OIG studies that had been commissioned at the time, which hinted very strongly that the postoperative portion of the global surgical package was overvalued. In an attempt to better quantify the true value of the global surgery package, the physician time spreadsheet was created for the purpose of ongoing assessment and (where applicable) revaluation of procedures codes via RVU tweaks. While the push to eliminate global periods was later abandoned by CMS, the physician time spreadsheet continues forward as a data set.

When the spreadsheet is opened, you will find it is split into 20 columns, the first being “CPT Code” and the last being “Total Time.” In between, five columns first appear that break down the time in categories that represent different stages of the global package of a procedure:

- Pre-Evaluation Time

- Pre-positioning Time

- Pre-service Scrub/Dress/Wait Time

- Median Intra-Service Time

- Immediate Post-Service Time

The times indicated in these different fields vary from procedure to procedure, based on complexity.

The remaining 13 fields are less clear about what they represent, but no less important to understanding the data set. Each column is headed by a different Evaluation & Management (E/M) code. There are six outpatient E/M services (99204, 99211 thru 99215), three subsequent inpatient E/M services (99231 thru 99233), discharge codes 99238 & 99239, and critical care codes 99291 & 99292. For many CPT codes with 10-day global periods, these services are indicated uniformly with a zero. For more complicated procedures where numbers greater than zero are indicated, these columns should be interpreted as, “in a typical global period for this procedure, it is expected that the equivalent of these E/M services will be performed.”

In the setting of CMS considering the elimination of global periods, what we would expect to see in a “post-global” world would be one allowance for the surgical procedure, and additional allowances for post-operative care. As one would expect, this would have a significant impact on current allowances for surgical services. This is more than likely the overarching reason why CMS has not explored the idea of eliminating global periods any further.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that we can’t learn anything else from this spreadsheet.

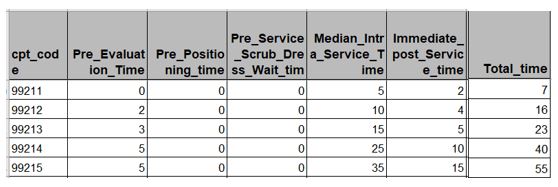

Let’s first look at E/M codes, particularly in the lead-up to outpatient E/M changes that will be instituted on January 1, 2021. As an illustrative example, we’ll look at CPT codes 99211 thru 99215 and the time values assigned to them by CMS for CY 2020:

For those of us who are E/M auditors, something jumps out almost immediately; the times indicated by CMS as part of its PFS do not match the times listed in CPT for the same codes. At first this is cause for concern, but allow me to calm your rattled nerves for a moment. While it is true that CMS calculates physician time via the data in the spreadsheet rather than times from CPT, know that the OIG only begins to notice total time for a year for a single physician when the total time reaches 5,000 hours. The most common reason for physicians reaching this mark is the employment of a physician assistant (PA) or a nurse practitioner (NP) billing supervised services under the NPI number of the physician, a practice known as “incident-to” billing. Unless there is a severe compliance concern based on aberrant billing patterns, usually the 5,000-hour threshold is explained by taking a deeper dive into the physician’s billing data. For this reason, when auditing for time, it is still best practice to audit to the CPT guidelines.

For those of us who are E/M auditors, something jumps out almost immediately; the times indicated by CMS as part of its PFS do not match the times listed in CPT for the same codes. At first this is cause for concern, but allow me to calm your rattled nerves for a moment. While it is true that CMS calculates physician time via the data in the spreadsheet rather than times from CPT, know that the OIG only begins to notice total time for a year for a single physician when the total time reaches 5,000 hours. The most common reason for physicians reaching this mark is the employment of a physician assistant (PA) or a nurse practitioner (NP) billing supervised services under the NPI number of the physician, a practice known as “incident-to” billing. Unless there is a severe compliance concern based on aberrant billing patterns, usually the 5,000-hour threshold is explained by taking a deeper dive into the physician’s billing data. For this reason, when auditing for time, it is still best practice to audit to the CPT guidelines.

Finally, I’d like to give surgical coders a reason to pay attention to this spreadsheet: Modifier 22 (increased procedural services). Modifier 22 is most commonly used when a surgeon encounters something unexpected in the course of surgery that increases the work required to complete the procedure. If the documentation clearly demonstrates the necessity for using modifier 22, additional payment above and beyond the usual reimbursement may be warranted. In order for this modifier to be considered for additional payment, the documentation must clearly show the following:

- A description of the complication / unusual circumstance encountered during the procedure;

- A description of the steps taken to address what was encountered; and

- The amount of time that was taken above and beyond what is normally encountered for the procedure.

If any of these are missing from the operative report, modifier 22 will not be considered for additional payment.

The biggest problem we encounter with modifier 22 is how to quantify the additional payment. It is on this last point where the physician time spreadsheet can provide some assistance. By calculating the additional time spent against the median time for the procedure, and then against the additional work applied to the surgery, it is possible to very closely estimate the amount of the additional payment you should receive when you append modifier 22.

At the very least, practices should become familiar with the physician time spreadsheet, and understand its applications in the present, and perhaps the future.